Why relationships aren’t just a ‘frilly extra’

Posted by The Cares Family on 24th November 2022

Please note: this post is 37 months old and The Cares Family is no longer operational. This post is shared for information only

This is an edited version of a keynote speech Rich Bell gave at the Relationships Project's Convening on Relationships-Centred Practice in Newcastle earlier this week.

Some of you will be aware that the Relationships Project talk about a spectrum of relationships-centred practice. This spectrum ranges from ‘Relationships as a means to an end’ to ‘Relationships as an end in themselves’ – and my organisation, The Cares Family, is very much at the ‘End in themselves’ end of this spectrum.

By Rich Bell

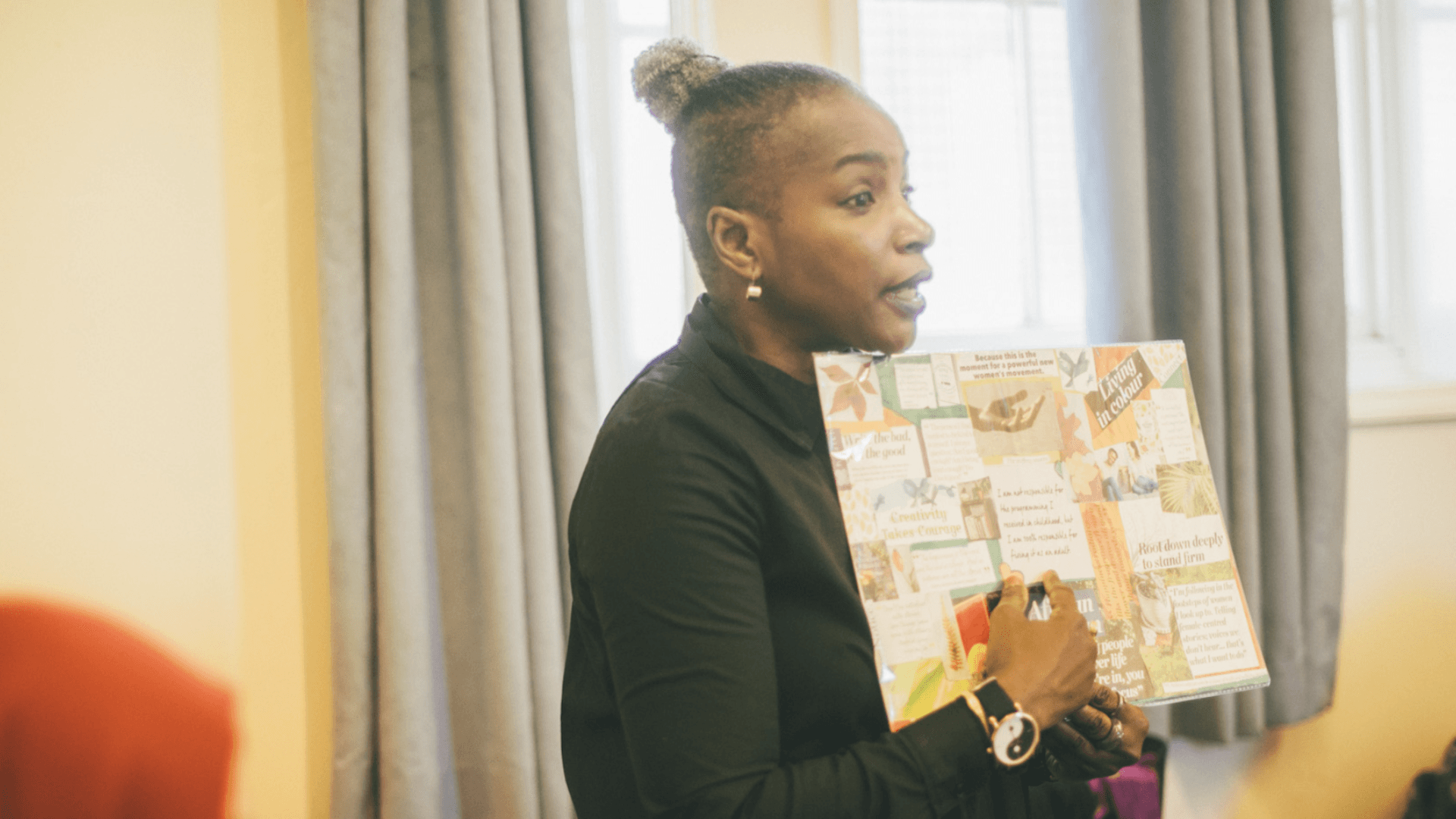

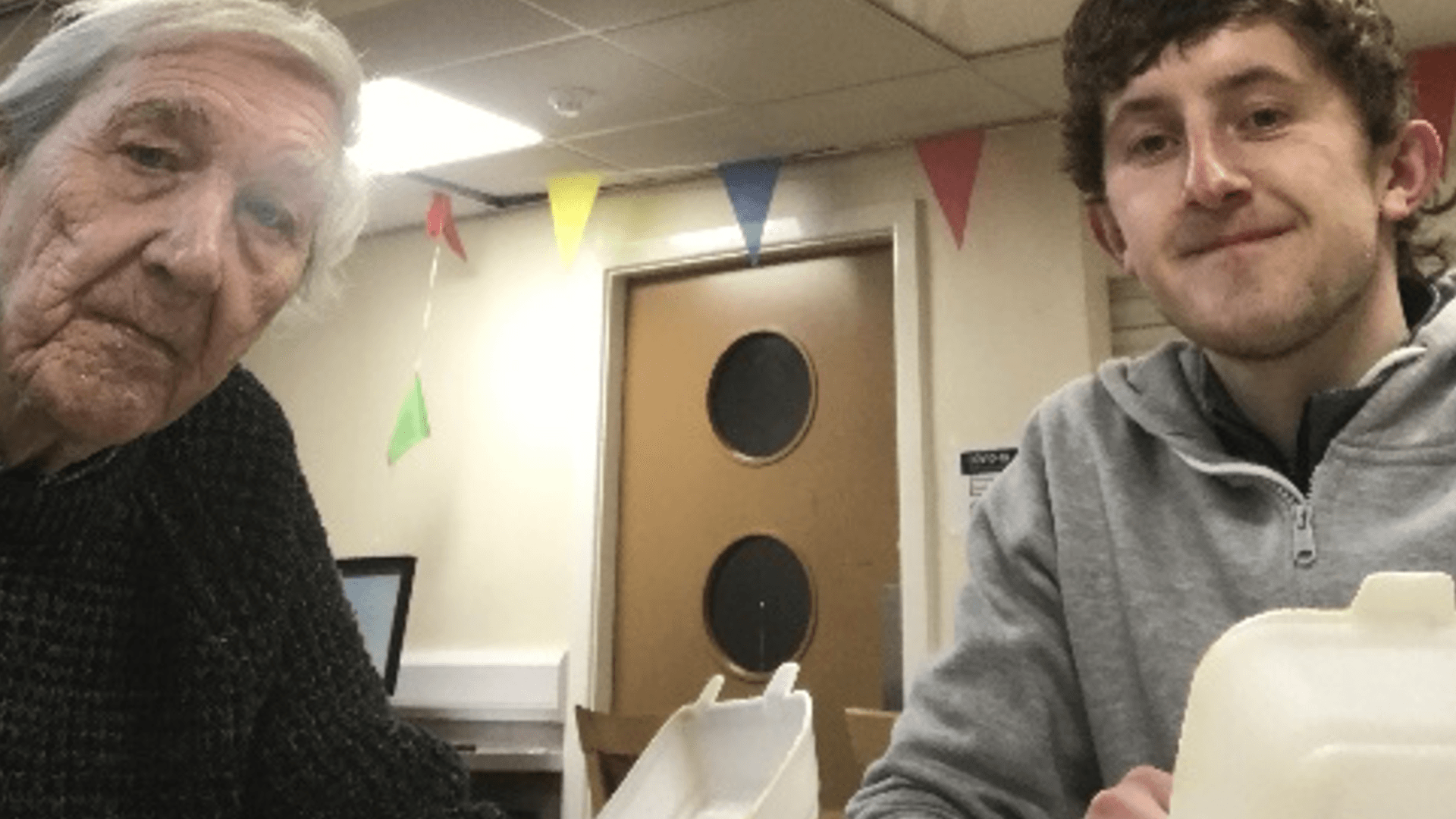

If you’re not familiar with Cares, we’re a family of charities which work to bring people from different generations and backgrounds – and with different experiences of life – together to build community and connection. Our work is all about tapping into and unleashing the power of human relationships.

Through our five local charities – North London Cares, South London Cares, Manchester Cares, Liverpool Cares and East London Cares – we bring older and younger neighbours together within their communities to share time, laughter and new experiences. And our national organisation seeks to bring about systemic and cultural change by seeding and supporting community-building initiatives across the UK and campaigning for policy action to strengthen social connection.

So, our work is rooted in a core conviction that our relationships with one another truly matter. And, today, I want to confront head on what I know is a response which sometimes runs through people’s heads when they hear me say that we’re a network of charities dedicated to creating more socially connected communities.

They hear me describe our mission and our work and they think: ‘Sure, OK. Social connection matters. Our relationships matter. But other things matter too. Things like food, warmth, jobs and decent homes. Our public services are being stretched beyond breaking point. Our charities and community organisations are overrun. Shouldn’t we really be focussing on that stuff?’

What I’m driving at is that the work of building relationships within communities and of fostering social connection can, when viewed from a certain vantage point, seem a bit ‘soft’, ‘fluffy’ or ‘frilly’. As [Relationships Project Founder] David Robinson said earlier today, it can be dismissed as nice but unimportant.

The work of building relationships within communities and of fostering social connection can, when viewed from a certain vantage point, seem a bit ‘soft’, ‘fluffy’ or ‘frilly’.

It’s Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, right? We’ve likely all come across this diagram, or a version of it, before. The American psychologist Abraham Maslow argued that our behaviour is driven by five distinct categories of human need. These categories are commonly depicted as hierarchical levels within a pyramid:

And people typically interpret this to mean that, before we can experience a meaningful sense of connection and belonging – let alone of purpose and accomplishment or of self-actualisation – our basic physiological needs and our deeply human desire for a degree of financial and physical security must be met. We climb up the pyramid, one tier at a time. It’s a straight, ascending path.

Viewed through this lens, the work of nurturing good relationships and of strengthening social connection is, unquestionably, a second order priority. And I’m sure that most of us would readily accept that, a lot of the time, that work – our work – genuinely should be considered as of secondary importance. Hunger, a lack of heating and unemployment are, as social challenges go, more urgent and, in that sense, certainly more important than loneliness, division and dislocation – that isn’t controversial.

I’m sure too that most of us would accept that we, as people, don’t empathise or connect as well with others when our basic needs aren’t being met. That’s clearly demonstrated both by empirical evidence and by the existence of the term ‘hangryness’. It’s common sense.

But – here’s the thing – it’s also common sense that we’re more likely to be able to attend to our own basic needs when we feel connected to other people. To whom do we turn to for help and support in tough times? To the people we know and trust – to our friends, family and neighbours, right? To our social networks. And this idea is borne out too in empirical research – for instance, a 2011 study found that, when someone who is long-term unemployed gains one close friend who is in work, they become 13 per cent more likely to find a job that year.

Surely, then, this begs the question of whether the relationship between the needs captured within the first two levels of Maslow’s pyramid – which might be described, broadly, as relating to our material living standards – and our degree of social connection is truly as linear as Maslow’s famous image implies. Of whether charting the path of that relationship is really as straightforward as putting one foot before the other and ascending to the next tier of the pyramid.

In point of fact, there’s a lot of evidence to support the idea that – far from strong and healthy relationships flowing from the sorts of economic conditions which support a decent standard of living – those conditions are themselves forged in the furnace of community and connection.

There’s a lot of evidence to support the idea that – far from strong and healthy relationships flowing from the sorts of economic conditions which support a decent standard of living – those conditions are themselves forged in the furnace of community and connection.

One way in which social scientists have sought both to measure and to underscore the importance of our relationships to one another is through drawing on the concept of ‘social capital’. This phrase has been defined by the sociologist Robert Putnam, who was made famous by his book Bowling Alone, as referring to ‘connections among individuals – social networks and the norms of reciprocity and trustworthiness that arise from them’.

In other words, it describes social ties and connections in a way which seems concrete, quantifiable and, well, ‘economicsy’ – and, low and behold, as a strategy to engage economists, the development of this concept seems to have worked.

At the macroeconomic level, social capital has been repeatedly demonstrated to be strongly and positively linked to GDP growth. This is – at least in part – as socially connected communities tend to be home to more fulfilled and productive employees. As businesses engage with one another more cooperatively and investors back entrepreneurs more readily in high-trust environments. As people support local businesses more actively when they feel rooted within local places. And as social networks enable knowledge exchange, in turn facilitating the spread of money-generating ideas and innovative practices; helping people to find the right jobs for their skill sets; and drawing more perspectives into collective problem solving.

It's also true that communities with higher levels of social capital tend to have higher levels of social mobility. Bridging social capital, or ties with members of other social groups, is particularly important in this respect. That’s in part because our developmental outcomes are shaped largely by the people we encounter early in life. And because we amass knowledge about how to behave, speak or dress in certain situations through meeting and mixing with people from different social and cultural backgrounds when we’re young and pliable. In societies in which people don’t mix and connect across class and cultural divides, then, economic and social inequality spanning generations becomes yet more entrenched.

In addition, several studies have shown that having access to a strong and diverse social network substantively boosts our chances as adults of finding new and better paid jobs and of gaining the trust of our employers.

Of course, two things can be true at once. As David also said earlier, we must reject false choices.

We can accept that people experiencing the ills of deprivation or precariousness are unlikely to connect with others as well as those whose basic needs are being met and who feel financially and physically secure; while also pointing out that less of us would experience those ills in the first place if more of us were better connected to those around us.

But the upshot of this conclusion is surely that a state and social system which too often treats the work of nurturing good relationships and fostering social connection as a ‘frilly extra’ or as the ‘last mile’ – which was built largely to respond only to the needs located at Maslow’s first and second levels – is in need of a fundamental overhaul.

At Cares, we believe that the decisions we make in our politics about how our lives and communities should be organised and the choices we make as changemakers and public servants about how our institutions and services should be designed should, in future, reflect a much more fulsome recognition of the transformative power of human relationships.

A recognition that, while material living standards matter hugely, perhaps more than I can describe, so do social living standards. And that, while hunger, a lack of heating and unemployment are truly urgent and deeply critical social challenges, cultivating community is one of the most effective ways in which we can head them off upstream.

A state and social system which too often treats the work of nurturing good relationships and fostering social connection as a ‘frilly extra’ or as the ‘last mile’ – which was built largely to respond only to the needs located at Maslow’s first and second levels – is in need of a fundamental overhaul.

More to the point, I wanted to focus particularly today on the relationships between social capital and economic opportunity and growth, because those are the parts of this picture which are, I believe, most commonly obscured. But strong and diverse social networks have also been shown to boost individuals’ health and wellbeing as well as social cohesion and the capacity of communities to exercise power collectively and well. So, our relationships with one another truly matter in manifold ways.

At Cares, we drew together the academic and think tank evidence which supports each of these points in a report which we produced last year with Power to Change, which is entitled Building our social infrastructure and is linked to in our welcome packs.

Strong and diverse social networks have also been shown to boost individuals’ health and wellbeing as well as social cohesion and the capacity of communities to exercise power collectively and well.

I also want to touch very briefly today on another project which we’re currently working on, and which is aimed at identifying the techniques and tactics which our team members draw on to support older and younger neighbours to connect meaningfully and positively. For the sake of time, I won’t go into what we’ve established through this work in detail, but we’ll be ready to share more news on this work soon.

The point I do wish to make now is this: we must all find ways of demonstrating that nurturing connection is not in any way unskilled work.

We’ve all personally experienced atmospheres and activities which felt conducive to getting to know those around us, and those that didn’t. And it’s also well-established that most of us instinctively find it easier to connect with those in whom we see something of ourselves. It follows that supporting people to connect well – across social, cultural and generational fault lines especially – takes intention, know-how and no small amount of skill.

Supporting people to connect well – across social, cultural and generational fault lines especially – takes intention, know-how and no small amount of skill.

Until we make that point understood, people will continue to assume that this work will, somehow, take care of itself and doesn’t require active support or investment; and our relationships to one another will continue to be systematically deprioritised.

It’s so as to disrupt exactly that assumption that we at Cares have begun to use the phrase ‘connecting institutions’ to describe organisations and initiatives which work in purposeful ways to support people to connect meaningfully and positively, including across difference.

In January, we’ll publish a new policy paper setting out the ways in which the government and those in positions of power might spur on the development of new and existing connecting institutions. Ultimately, though, we share the Relationship Project’s conviction that the change we seek will only be brought about if we, as a community of social fabric weavers and bridge builders, come together in common cause.

Hopefully today will mark an important milestone on our journey to that very destination.