What does it take to improve a place?

Posted by The Cares Family on 9th April 2018

Please note: this post is 94 months old and The Cares Family is no longer operational. This post is shared for information only

By Alex Smith

Everyone has their place. On the most basic level, that place could be little more than a specific geography – a location, a dwelling, a spot. More often, places are about feelings. Who could argue that a ‘home’ is made up simply of bricks and mortar and not the combination of comfort, contentment and connection? But most powerfully, places are about roles: a position on a football team; a specific insight brought to a group; an individual contribution to a collective purpose, defined by context and played out in relation to others.

The question of how to improve a place, then, is a sticky one – layered with subjectivity and nuance. And yet, at some level, we all want to improve our place – whether our social status, our financial position, our level of responsibility, or our communities. This essay is about communities – not so much our shared physical spaces, but more the ways in which we choose to interact with one another, and how the systems and structures that we have established to do so may help or hinder those interactions.

Specifically, it is about building organisations to bring people from different backgrounds and life experiences together, as we have done with North London Cares, South London Cares and Manchester Cares (collectively The Cares Family) over the past seven years in an attempt to reduce loneliness in rapidly changing urban environments. So while the experiences and examples may be unique to our own exploration, there remain some themes that I hope everyone with a stake in their communities may find helpful. Namely, those universal themes are: agency, authenticity, action, attitude, agility and accountability.

Theme 1: Agency

Our first branch opened in 2011, almost a year after a small interaction changed my life. Back in 2010, I’d been a council candidate in the area where I grew up, and on election day, knocking on doors to drum up votes, I met a frail 84-year-old man named Fred.

Fred told me that he’d love to come out and vote. He’d never missed an election in his life. But he would have to forgo his role in our democratic process this time, he said, because he couldn’t get out – indeed, he hadn’t been out of his house in three months. With a wheelchair poking out of the corridor behind him, I suggested that, if he was comfortable, I could escort Fred to the voting place. While we were out together Fred became animated: it was a joy to speak to people after so long. But what he really craved was a haircut. The next day, having lost my election, I wheeled Fred down the road again, this time to our local barber shop.

While Fred was in the barber’s chair, he opened up. He told me about his life. He’d been a performer on the cruise ships, and played the London Palladium in the 1950s. Later, he’d set up the business that was my favourite place as I grew up in Camden Town – the fancy dress shop Escapade. I couldn’t believe that, some twenty years earlier, I’d spent time with Fred as he sold me Halloween costumes. Over the following weeks and months, Fred and I built a friendship – and he inspired the idea of bringing young professionals and older people together for the benefit of all participants.

I don’t tell this story through some fond nostalgia, but because it still defines something at the centre of what it takes to improve a place. Through the diminishing of his social networks, Fred had lost his agency, and fallen into isolation. But through our shared visits to the voting station and the barber shop – places familiar to both of us – and through our shared storytelling, we had both felt more in control. We gave one another something important: that sense of being connected to the people and places around us.

But Fred had also awoken in me another realisation – that people in communities have the power to help one another outside of formal systems and structures which, in their remoteness, can often leave people feeling alone. My experience with Fred taught me that we don’t have to wait for big government, big business or big charities to fix the problems in front of our eyes. On the contrary, if we do, some of those biggest challenges may never get solved.

The Cares Family, which has now created 250,000 interactions between 5,000 younger and 4,000 older people, works because it is a resolutely grassroots organisation. And I’ve been reminded time and again in the last seven years that, for all our growth, it’s those interactions and the shared power they create which matter most.

Theme 2: Authenticity

The Cares Family’s founding story reminds me of something else too: that language and narrative are fundamental to how we perceive our place, and by extension how we improve it.

If Fred had ever felt that I was offering a ‘service’ by escorting him to the barber’s, there’s no way he’d have agreed to it. Fred is a proud man with a rich personality and heritage. He didn’t want to be ‘done to’. He was not my ‘client’ and I was not ‘befriending’ him. Neither of us was a ‘beneficiary’. We were just neighbours. At a time when corporate language permeated every aspect of our public sphere, that authenticity and parity were fundamental.

And they still are. The Cares Family has necessarily had to professionalise in some ways as we’ve grown up but we still reject the language of service provision in favour of an altogether more communitarian approach. Our model does not seek to ‘empower’ people – because people already have intrinsic power. Rather, our objectives are to ‘bring people together’ to ‘improve connection, confidence, resilience and power’ – and to reduce loneliness through real, mutual relationships.

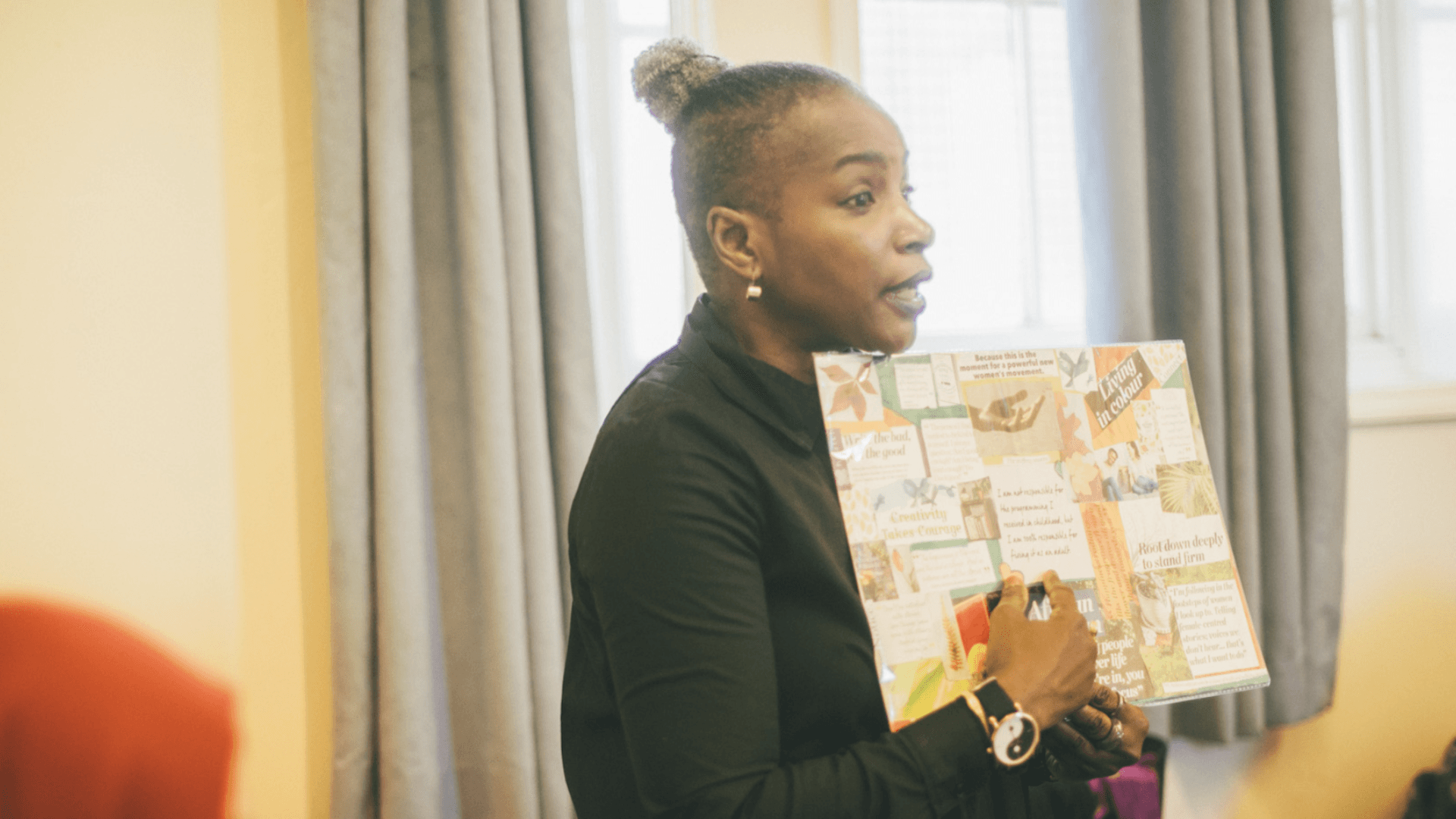

Importantly, we have always sought to do the things that people tell us they want to do. In our experience that has rarely been bingo and knitting, or creating digital connection through online apps. Instead, young professionals have invited their older neighbours to share lunches in their tall glass workplaces, and in local pubs and cafes – those familiar but often changing places that can feel marginalising for some but should surely be places to share.

In return, older people have invited younger neighbours into their homes – to share 95th birthdays, Christmas parties, board games, photos and Friday night fish and chips. Those interactions offer the chance for people to share stories about their lives, and to feel valued and visible. And those stories don’t only connect people to the past – they also connect younger and older people alike to a shared future.

Theme 3: Action

If agency and authenticity are crucial to improving a place, then so too is action. Recent studies have shown that while people value community, many are increasingly withdrawing from it. This is evident in falling participation in faith groups and trade union memberships, among other traditional community outlets. And while we are spending more time with close relatives than ever, we are spending less time with people in our wider neighbourhoods around us. Subsequently, we feel that the country at large is dividing – on attitudes, on our openness to the world, on politics, and through the filter bubbles that refract more heat than light.

All of this points to an urgent need for action. If we value something, we have to work hard to protect it, and to nurture it. So if traditional structures are diminishing, new ones will need to be created. With the agency of authenticity, many are already appearing – from The Sunday Assembly, to GoodGym, to Chatty Cafes, to Future First, to Girl Gang, to NCS and many others all around the country.

Theme 4: Attitude

Clearly, there is some element of circumventing or supplanting existing power structures in this approach. That takes a particular mindset and a hope that there must be a better way to organise our communities to make them fit for a rapidly changing world.

So hardwired into The Cares Family’s attitude – and our stated value framework – are ‘adventure’ and ‘originality’. This translates into a willingness to take risks. At different stages in The Cares Family’s development we have been opportunistic. We launched spontaneously in summer 2011 by encouraging young people to help with the clean-up after the London riots. Later, we piloted other projects with little relation to our core objectives as a way of testing our processes and honing our model. And while it was never our original intention to replicate The Cares Family across the river, when we could see that young south Londoners – and indeed Mancunians – were just as passionate about spending time with their older neighbours, we grafted to find a way to expand our work and to do so in a way that was built on the personality and passion of places.

In the earliest days – with no money, no strategy, no staff and no profile – we had to bootstrap the development of the organisation. Many were the times, in the first year running, when I thought that we would wind-up. But the more we spoke to people about our work, and the more open to collaboration we became, the more good people started to shape it: advisors became trustees, supporters became funders, friends recruited friends recruited friends to volunteer – and, most importantly, every staff member who joined, without exception, added their own fresh ideas and perspectives, honing the model year-on-year.

Of course, scaling an organisation at a time of change and chaos in public services as in society at large requires resilience too. So in our interview process we’ve always asked potential colleagues about their toughness and attitudes to risk and innovation, as well as our other stated values – kindness, warmth and passion. And increasingly, we seek to reflect these values in our day-to-day management practices and organisational culture.

Theme 5: Agility

In the chaos of that changing world, the fifth watchword that our experience tells us helps to improve a place is agility. That’s something we apply at the very core of The Cares Family’s model. For years, young professionals had been a ‘hard to reach’ demographic for voluntary organisations. In the digital age, the most traditional groups were still operating in analogue – creating bureaucracies or timetables that did not attract people with busy work and social lives. So we built our approach around our two target audiences, creating social clubs during evenings and weekends when young people are typically free and craving community, and older people told us they felt most alone.

Agility is also something we seek to apply to our internal culture. For the first two years running The Cares Family, we didn’t have the money to invest in an office so we squatted wherever we could – in partner organisations, in my kitchen at home, in coffee shops – until we began hot desking at Camden Collective, a shared workspace, in 2013. Our South London branch did exactly the same thing in the heart of its community in Brixton. It was only after five years that both London branches were secure enough to rent private offices – and we still have short term leases to this day. We’ve also been agile in our team building – hiring two fundraisers in 2016 instead of the planned one when we sensed an opportunity to expand our income; moving people between our the North and South Family Cares branches; and seeking to promote from within where possible.

Now, the whole of our model is based on that same need to be nimble. We don’t want our objectives to be determined by those big government, big business or big charity organisations, so we have evolved our income generation to be as organic and community-led as possible. 45% of our overall funds are now raised from within our networks – including through supporters doing marathons, giving small amounts of money each month or coming along to gigs, comedy nights and pub quizzes. And our federated governance model – with each local branch constituted separately but supported by an umbrella organisation led by the same six trustees – allows us to build communities based on their unique local identities while sharing economies of scale. That means we are led by the interests of the people and places we work with, rather than by remote central authorities.

Theme 6: Accountability

The relative freedom to build a model based on agility, attitude, action, authenticity and agency requires one final, fundamental tenet: accountability. Because, in order to improve your place, you have to respond to its changing needs, interests, culture and demographics. So we take seriously our responsibility to evidence, evaluation and safeguarding.

Seeking constantly to improve, in 2014 we invited a researcher to survey 150 older people and 150 younger people involved in our activities. Not everything we learned was comfortable. We weren’t reaching as many of the diverse communities in our urban communities as we’d have liked. We had lost contact with some volunteers because we weren’t communicating well enough; others we were losing altogether because of challenges in our capacity.

Our response was to develop a new function – Outreach – which enabled us to identify more older people where they were and to better mobilise young people through new inductions and communication techniques. And we took the time to create a comprehensive risk assessment, a 60-page policy document which we still review regularly, and unique monitoring tools which enable us to report on our specific outputs and outcomes.

All of these developments helped The Cares Family to develop as an organisation seeking to improve our places of community. But whether we’ve ever fundamentally changed our place at all remains a matter of contention.

Our work seeks to soften the isolating effects of rapid community change resulting from globalization, gentrification, urban transience, digitization and housing bubbles. It also aims to bring people together across social, generational, digital and attitudinal divides to reduce loneliness. For the people who are involved in our work, we have evidence that we do achieve those ambitious objectives.

And yet the big picture forces which continue to leave people feeling left out and left behind continue to strengthen. Those trends may be beyond our control. But in that context, it is ever more important to help people feel they are part of their changing world, rather than left behind by it – and to make sure everyone feels they have a place to call home.

This essay was first published by Renaisi.