Our social capital crisis and why it matters – Part three (fortifying our democracy)

Posted by The Cares Family on 9th December 2021

Please note: this post is 40 months old and The Cares Family is no longer operational. This post is shared for information only

The Cares Family and Power to Change recently jointly-published a new report, Building our social infrastructure: Why levelling up means creating a more socially connected country. This report argues that, in order to level up Britain, Ministers and officials should put relationships and communities at the heart of policy and decision-making. Over the coming months, we will post a series of blogs exploring and summarising the key findings and points set out in it. This is the third of these blogs. The first can be found here and the second here.

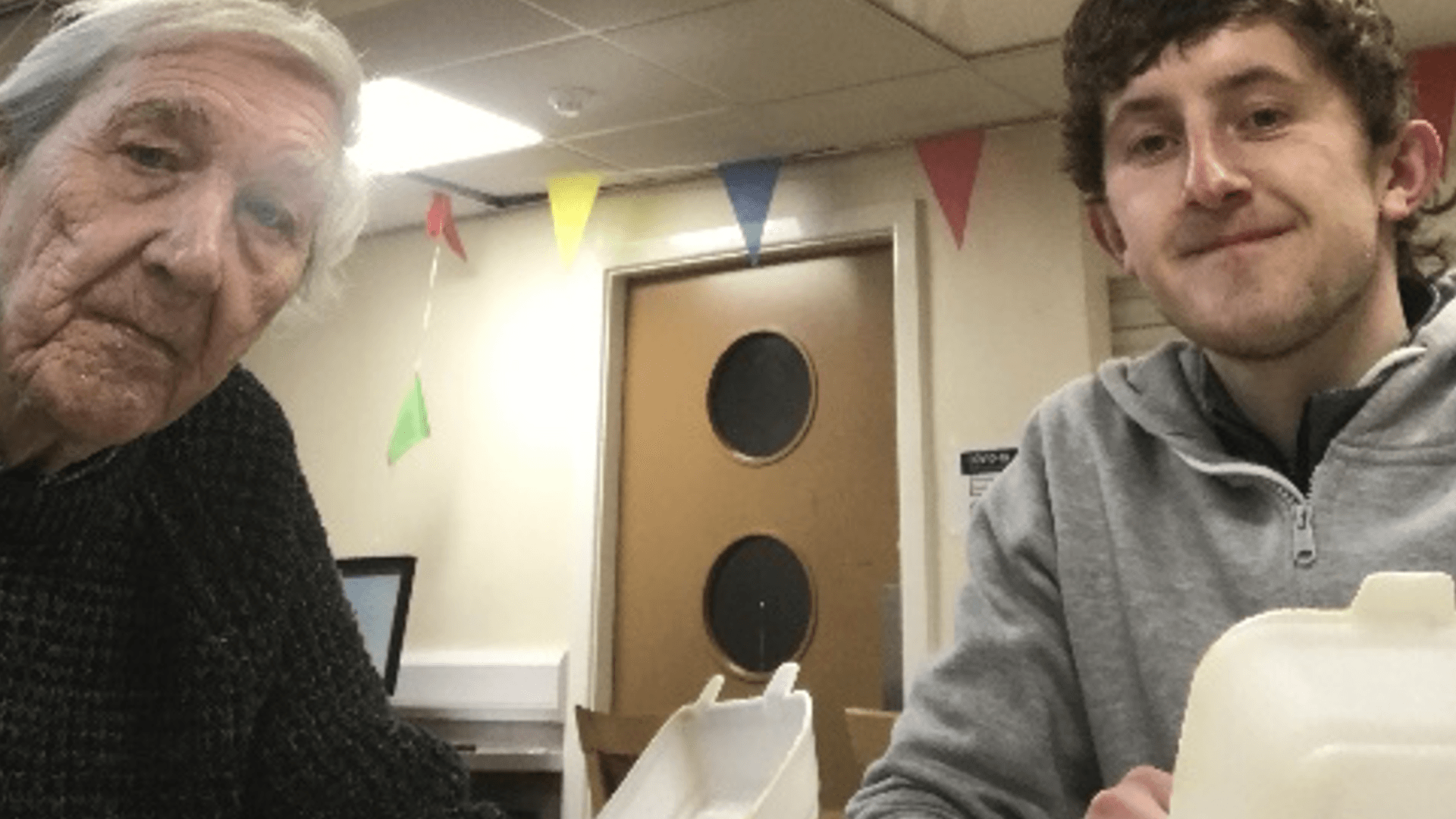

Just over four years ago, the former Cabinet Minister Douglas Alexander made a radio programme exploring the way in which people in modern Britain increasingly live ‘parallel lives’ – mixing and building relationships only with those who are like them. The programme, A Culture of Encounter, features an interview with Roy, who was then 70, and Jack, who was 29 – two friends who met through South London Cares’ Love Your Neighbour programme.

Among other things, Jack and Roy speak about how, when it comes to politics, they don’t always agree – how they voted for different parties in the 2017 General Election and for different sides in the Brexit referendum that had taken place the year before. But they both also attest that, through forging a friendship, they have come to understand the other’s perspective in a way they didn’t before. They still might not see eye-to-eye, but they looked into one another’s and saw someone doing their best.

4 years ago, Roy featured on this @BBCRadio4 documentary, ‘A Culture of Encounter’, with his @SouthLDNCares friend Jack and @D_G_Alexander.

— The Cares Family (@TheCaresFamily) October 28, 2021

Encountering people from different walks of life is part of the richness of life. Here’s to many more friendships.https://t.co/zkvDWZWlbS https://t.co/u7HcoX867w

Through this series of blogs, I have sought to unpack how our individual experiences of social disconnection cumulatively shape our communities and country. In part one, I set out how our social capital crisis is impeding economic growth and restricting social mobility. In part two, I explored the ways in which loneliness and division are at once taking a huge toll on our health and wellbeing and thwarting exactly the sort of preventative, community-based approaches which might alleviate the ensuing pressure on public services. This blog will investigate disconnection’s impact on a yet more vital dimension of our shared national life – our democracy.

Often, we are too quick to assume that the same process of polarisation which has left democracy teetering on the brink Stateside is underway on our side of the Atlantic. In actual fact, a landmark 2020 study from More in Common found that our country has fractured into several subtly different political tribes – not two fundamentally opposed ones as appears to be the case in post-Trump America. Nonetheless, the evidence that the UK has become more polarised as a result of the Brexit referendum and its fallout – as we have come to identify more viscerally with the political identity of Remainer or Leaver than with any party – is clear and compelling.

Analysts have convincingly demonstrated too that this marked change in how we think and speak about our political identities reflects a broader trend towards a political debate centred on social and cultural values rather than economic interests. Even as the UK as a whole has become decidedly more liberal in its social views, deeper attitudinal divides have risen to the surface. We have come to cast our ballots more and more based on the level of importance we attach to respecting traditions, obeying rules and maintaining the prevailing social order and less and less according to where we fall on the left-right spectrum.

Our political parties, on the other hand, continue to define themselves largely by their views on public spending and the size of the state. Indeed, it could be argued that our country hasn’t descended into the same quagmire of extreme polarisation in which the US now finds itself in large part because our major parties have remained relatively firmly rooted in left and right-wing economic traditions and ideologies. Neither the Conservatives nor Labour are as yet viewed as unambiguous standard-bearers for a particular set of social and cultural values, so Remainers and Leavers continue to find a home in both big parties – for now.

Indications that this is changing as our political leaders seek to reconcile the demands and interests of diffuse and shifting electoral coalitions should, then, worry us deeply.

Our social attitudes are, after all, shaped in no small part by our backgrounds as well as by the extent to which predominant cultural views enable us to feel that we belong in our communities and society. It follows that political parties which start to speak only for people who hold to certain social values soon come to have less to say about the interests of those with different experience of life and of society as a whole.

And, at a deeper level, the realignment of our politics which may be underway may also have ramifications far beyond the political arena – shaping our sense of who we are at our cores and dividing society in profound and dangerous ways. How this might come to pass is a matter which it would take a whole blog to unpack, which is why we’ll devote the next one in this series to doing just that.

This blog has already deviated significantly from its stated intention of summarising the key points made within our recent joint-report with Power to Change (which doesn’t really get into any of this stuff), and my next few blogs will in fact veer even further off-road. This is in part because the impact of social disconnection on our democracy is a subject which The Cares Family hopes to explore further in 2022 and, it being December, we’re thinking ahead to what’s to come. It’s also because the changing relationship between our individual political, cultural and social identities is key to why we need to act now to tackle our social capital crisis and forge a more connected country.

Maybe, just maybe, the answer to the problem of rising polarisation and political division doesn’t lie solely in changing the way we debate issues in the media or online, in reforming our electoral system or in picking different politicians. The next few blogs in this series will argue that the solution to this challenge – or a big part of it, anyway – lies instead in supporting more people to take their cues from Roy and Jack and connect meaningfully across social and cultural cleavages.

The next blog in this series is here.