Our social capital crisis and why it matters – Part one (building a strong and fair economy)

Posted by The Cares Family on 10th November 2021

Please note: this post is 49 months old and The Cares Family is no longer operational. This post is shared for information only

The Cares Family and Power to Change recently jointly published a new report, Building our social infrastructure: Why levelling up means creating a more socially connected country. Our report argues that, in order to level up Britain, Ministers and officials should put relationships and communities at the heart of policy and decision-making. Over the coming month, we will post a series of blogs exploring and summarising the key findings and points set out in it. This is the first of these blogs.

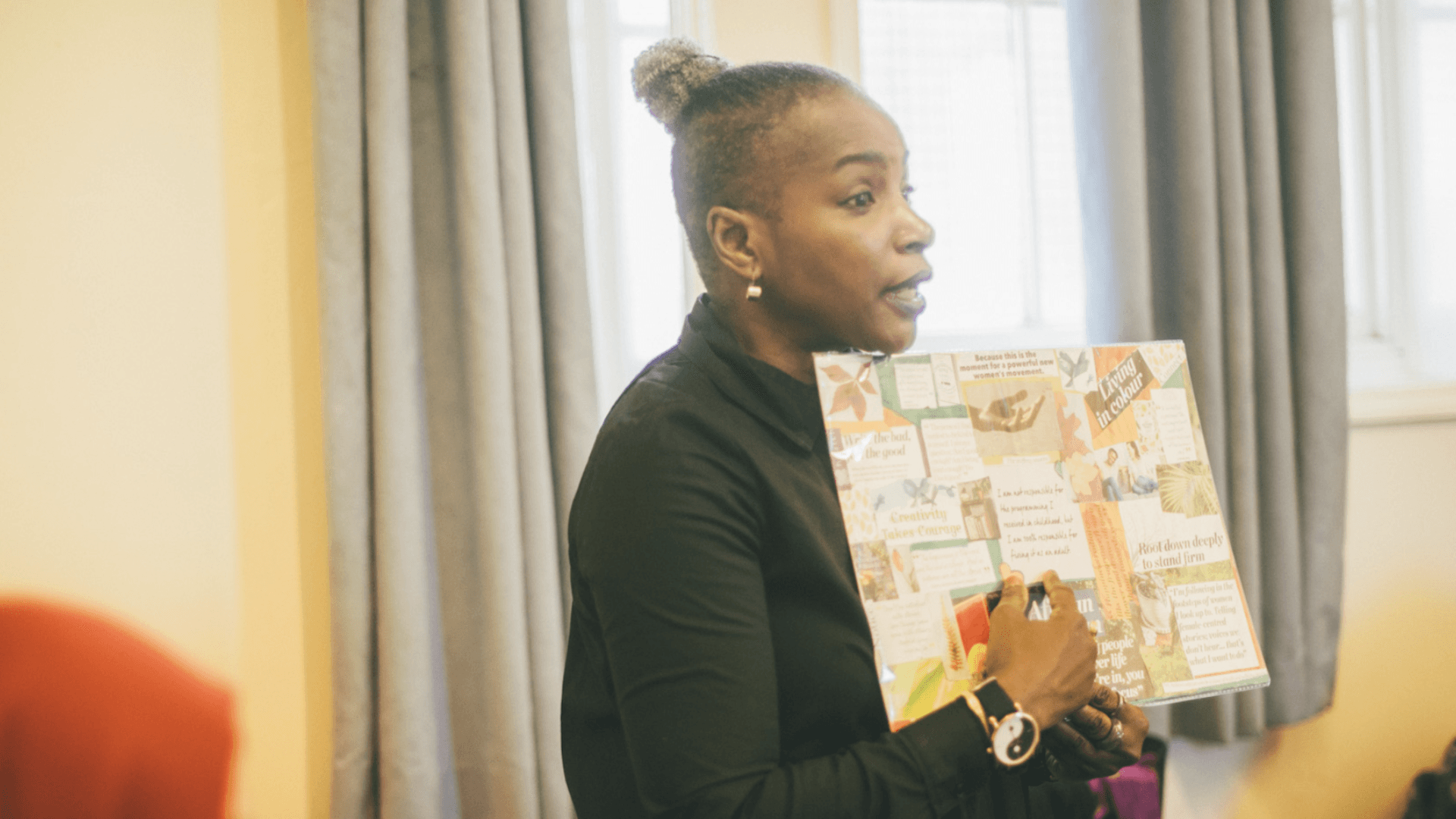

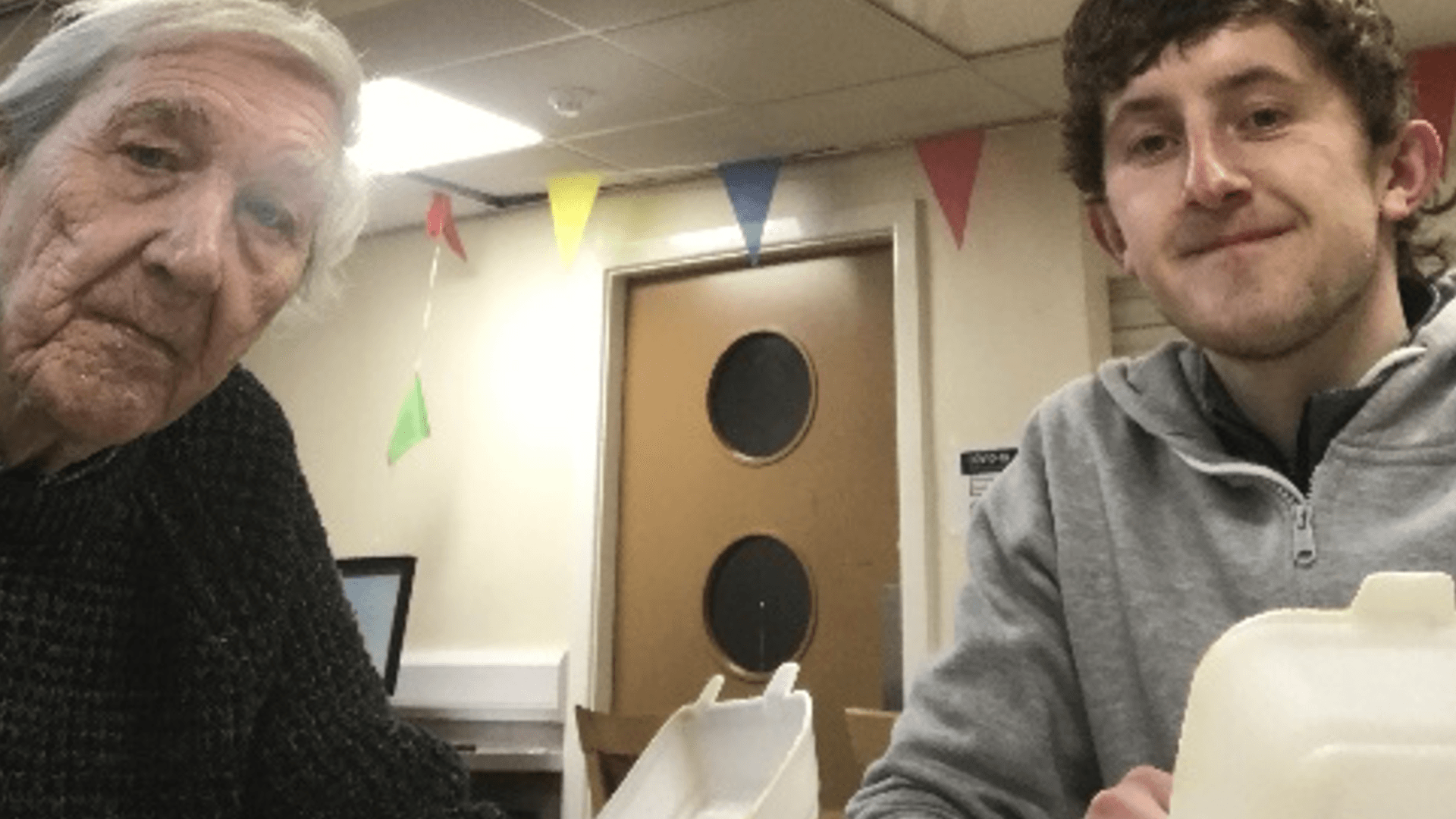

At The Cares Family, we have long argued that the UK is experiencing a deeply pernicious crisis of disconnection. Take, Marion, 83, and Sarah, 50. Marion has lived in the same corner of north London for decades, but the rapid pace of change in her area has left her feeling untethered from the community she’s called home for so long. Sarah on the other hand struggled to feel that she was a part of her community upon moving to London from Manchester. We’ll hear more about Marion and Sarah’s experiences as this series of blogs progresses, but theirs are just two of the personal stories of dislocation which we’ve been surfacing for over 10 years. More recently, we’ve made the case that social disconnection, as well as being a personal crisis for so many, is a public and political crisis too.

Sarah and Marion both joined North London Cares, and during the pandemic were connected to one another through our Love Your Neighbour programme. They cite each other as the thing that helped them cope during the worst of the pandemic.

So we were struck earlier this year when RSA chief executive Andy Haldane, in his inaugural Community Power lecture for the Local Trust, suggested that our country is in the midst of “a crisis in social capital” – in “trust and engagement, relationships and reciprocity, communities and civic institutions”.

Social capital was defined by the American political scientist Robert Putnam as referring to “connections among individuals – social networks and the norms of reciprocity and trustworthiness that arise from them”. Social capital, social connection – potato, potatoh, tomato, tomatoh.

Andy Haldane has since been appointed the chair of the government’s levelling up task force, and several recently published reports have shone a light on how our social capital deficit is compounding many of the challenges which the levelling up agenda is intended to address. One such report by Onward argues compellingly that community ties and pride in “left behind” places have faded as the economic health and physical infrastructure of those areas has degenerated, but also as the local institutions and relationships which once underpinned feelings of belonging, security and wellbeing have waned.

Our new joint-report with Power to Change seeks to contribute to our shared understanding of this emerging evidence base by drawing together the available evidence as to how a deficit of social capital is holding back communities across the UK.

We wanted to set out, in straightforward terms, why a lack of connections among individuals is impacting so negatively on our society and economy.

Most of us tend to believe that our relationships hold significance for ourselves and for the people in our lives, but not for society at large. In light of that fact, it’s not enough to point out – for instance – that social capital has been shown by a number of major studies to be strongly associated with GDP growth at the macroeconomic level. In order to win hearts and minds, proponents of the power of social connection are going to need to do a better job of unpacking what exactly ‘relational wealth’ and economic prosperity have to do with one another.

As our new report explains, economists have demonstrated that:

- Lower levels of community engagement and activity result in higher rates of ill health and unhappiness, generating significant productivity costs;

- Businesses are more likely to engage with one another co-operatively in high-social trust environments;

- The development of trusting relationships within and across communities facilities the flow of both investment and money-generating ideas;

- People are more likely to seek to actively support local businesses when they feel at home in and attached to their local areas.

It’s also true that where people build strong and diverse social networks, opportunity is spread more evenly across communities. Researchers have found that division stifles social mobility – which is itself positively associated with productivity and growth – as:

- Our developmental outcomes are shaped largely by the people whom we encounter early in life;

- Our ability to access opportunities through family networks depends upon who’s a part of those networks;

- Mixing with others from different social and cultural backgrounds allows young people to acquire valuable knowledge as to how they are expected to behave, dress and speak in certain situations;

- Having access to a diverse network of social contacts helps adults to find new and better-paid jobs and to gain the trust of their employers.

It’s been empirically proven, in other words, that it’s often not what you know but who you know that matters.

There are promising signs that the impact of our crisis of disconnection in impeding economic growth and hampering fair access to opportunity is beginning to register in our political debate. An encouraging new pamphlet co-signed by ten Conservative MPs attests that it is not that places are “wealthier and happier and therefore have a high density of local civic institutions. They are wealthier and happier because they have a high density of local civic institutions.”

Wealthier and happier, and healthier and more powerful too – as part two of this blog will outline – but we shouldn’t breeze past the significance of that last statement. A political and policy agenda rooted in the reality that thriving and fair economies spring from strong communities would be grounded too in the power of relationships to shape and change lives. It is an agenda of that sort that we hope to play a part in nurturing through our work in spelling out exactly how our social capital crisis is holding Britain back.

The next blog in this series is here.