Our attitudinal divisions and the rising risk of rupture – Part one

Posted by The Cares Family on 13th December 2021

Please note: this post is 40 months old and The Cares Family is no longer operational. This post is shared for information only

The Cares Family and Power to Change recently jointly-published a new report, Building our social infrastructure: Why levelling up means creating a more socially connected country. This report argues that, in order to level up Britain, Ministers and officials should put relationships and communities at the heart of policy and decision-making. Over the coming months, we will post a series of blogs summarising the key findings and points set out in this report and exploring related themes. This is the fourth of these blogs. The first can be found here, the second here and the third here.

Most of us have far more in common than we’ll ever have the chance to know. At The Cares Family, we take great pride in giving people who likely wouldn’t otherwise meet the time, space and opportunity to discover that they’re not so unalike after all. Often, the older and younger neighbours who come together through our programmes find that, despite being born decades apart and having led very different lives, they’re driven by the same passions. Anne, 71, and Trish, 30, whose story was told by the Manchester Evening News earlier this month, met at a Manchester Cares pub quiz and soon got to talking about all that they share, including a love of Manchester United.

Football is frequently found at the core of great friendships. In my last blog, I began to set out the case that the increasing centrality of social and cultural values in our politics may eventually divide society in profound and dangerous ways. If we’re to wrap our heads around why that’s so, we need first of all to ask ourselves why cheering on the same club is so often such a powerful bonding experience.

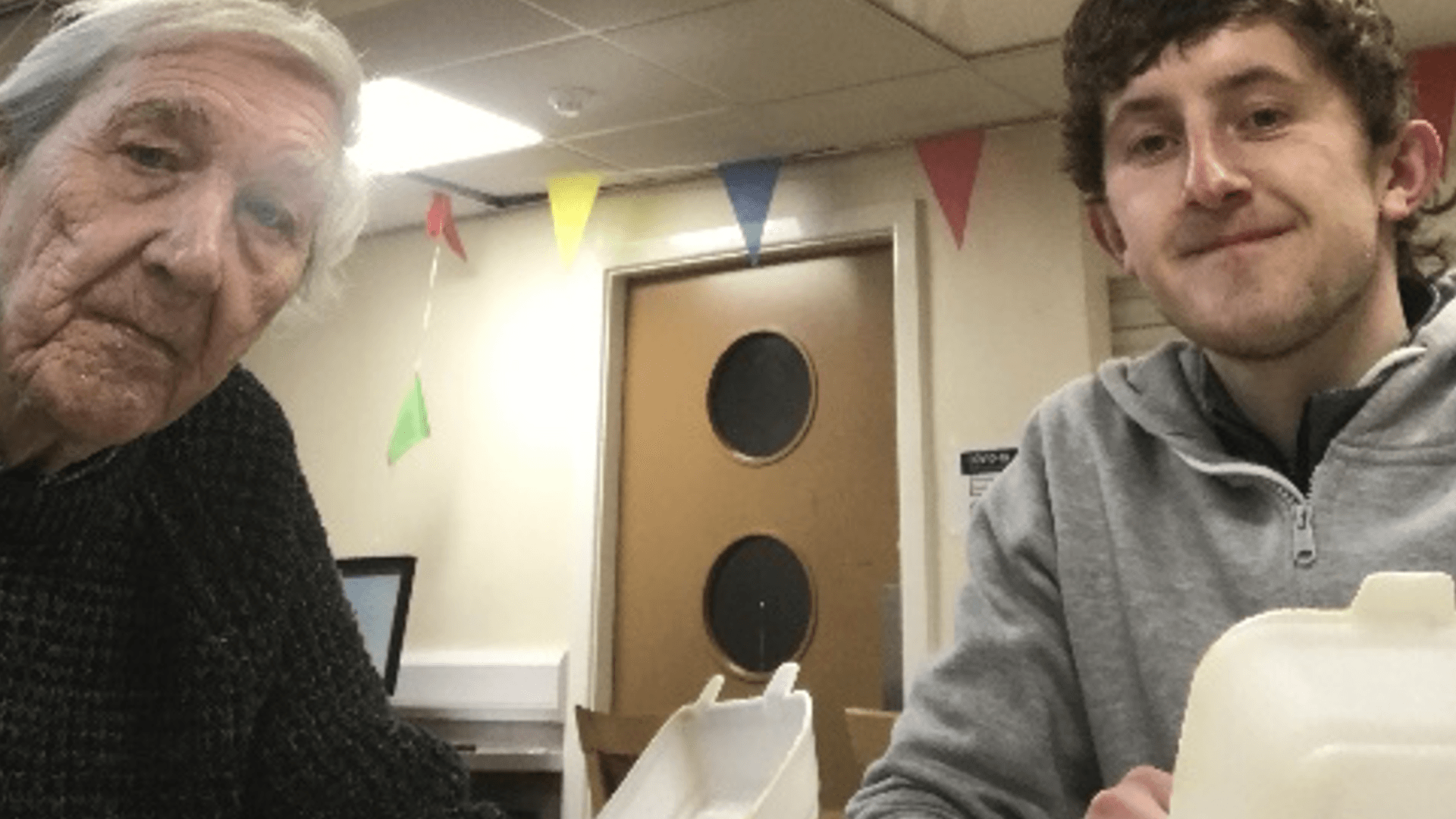

Anne and Trish at a recent Manchester United match

Maybe it’s because of the up-and-down emotions inspired by a back-and-forth match; because of the physical feeling of unity we experience when the crowd around us swells in unison; because of the sure-fire knowledge that, for these ninety minutes, it’s our team versus their team; or because of the shortcut to solidarity offered by colourful shirts and scarfs and sometimes even more colourful chants – but there can be no doubt that football is a powerful source of shared identity and, as a result, of pride. Whenever a sports team we support wins or performs well, we derive very real feelings of personal satisfaction, even in the full knowledge that we personally played no tangible part in their achievement.

We're partial to colourful shirts ourselves

The same goes for when our country does well at the Olympics or at Eurovision; when our city or town is productive and flourishes; when our religious group thrives; when a political party which we associate with wins an election; or when some other social or cultural group which we consider ourselves to be a part of succeeds in some way. We are, ultimately, tribal animals. As the political scientist Lilliana Mason has argued powerfully, each of our shared or group identities are important sources not just of belonging and meaning but also of self-esteem. Our sense of our own status rises and falls with the exploits and prospects of those groups to which we feel we belong.

That’s natural and not unhealthy, but problems arise when these group identities come to overlap and bleed into one another. Each of us can, after all, belong to only so many tribes and so is able to draw from only so many wells of self-esteem. When they become too closely bound up with one another – when, in Mason’s telling, our political, social and cultural identities fuse to form partisan ‘mega-identities’ – it’s sort of like we’ve put a bunch of eggs that we’re weirdly attached to in a single basket. If and when it’s knocked over, so are we.

By the same token, the Brexitification of British politics – and the broader realignment towards a politics centred on social and cultural values which it has at once revealed and accelerated – doesn’t just mean that our political contest is taking place on different terrain, but that we all have more eggs in our baskets come election day.

At the 2019 election, large numbers of Leave voters switched their political allegiance to the Conservative Party. If the furtherance of the Brexit cause continues to become one and the same with support for the Tories in the minds of those voters, then its defeat at a future election would likely hit them especially hard. They might feel not just that their preferred political party – and path forward for the country – had been rejected, but that their sense of the foundation stones upon which it should be built – their very worldview – had been too. More than that, they might feel that they and people like them had been personally rebuffed and overruled by another group who might seem to live in a different country entirely.

That’s because of the nature of that cause. When the referendum fell upon us, we seemed to slip into the roles of Leaver and Remainer as if they were the ones we were born to play. Arguably, we had been nurturing a sense of ourselves as patriotic defenders of common sense or as socially liberal citizens of the world privately for some time. These identities could already be detected in the people and pastimes we gravitated towards, in how we conceived of our national identity, in our consumer habits, in our cultural diets and in our actual diets – the Brexit debate simply gave them expression in our politics.

It bears repeating that we have not as yet been sorted into two diametrically opposed political tribes, but there can be little doubt that to be a Remainer or a Leaver is to inhabit one of Mason’s portentously partisan mega-identities. As deep attitudinal divisions over the social and cultural values which should shape our shared national life rise to the foreground of our political debate, so rises the risk of our society going the way of post-Trump America and rupturing, perhaps irreparably.

At The Cares Family, we do not by any means believe that our country is bound to crack apart like so many eggs. In fact, we believe that the solution to the challenge of growing polarisation and division is in some ways more straightforward than we’re typically led to believe. But we also believe that we need to face up to the full scale of the threat facing our democracy and the way it’s bound up with our own beliefs and worldviews. That’s no easy feat, not least because, once politics starts to mine this deeply into our sense of who we are as people, the earth beneath our feet can soon begin to feel awfully unsteady – as the next blog in this series will set out.

The next blog in this series is here.