A broader, richer culture

Posted by The Cares Family on 12th June 2019

Please note: this post is 78 months old and The Cares Family is no longer operational. This post is shared for information only

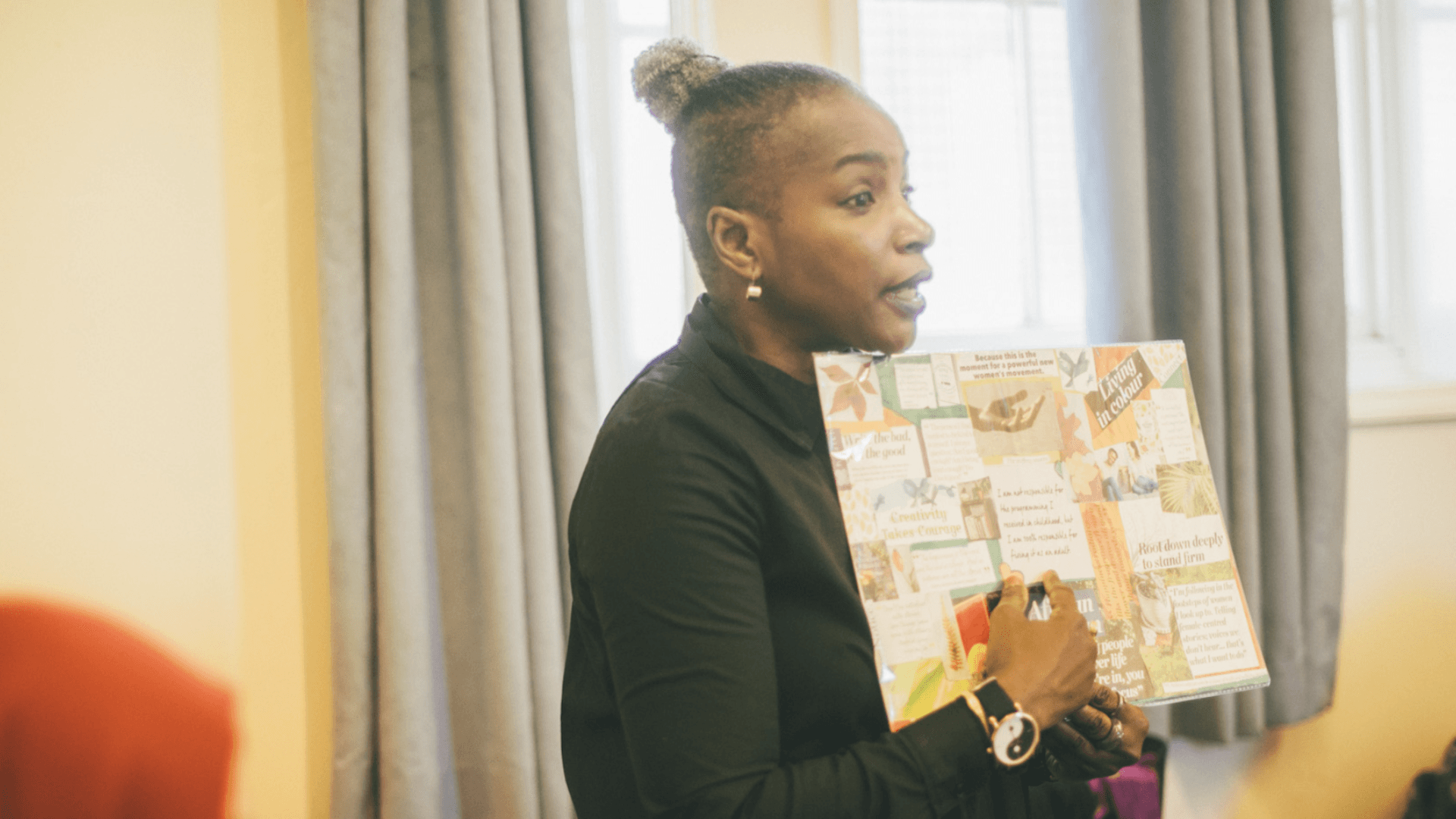

By Sade Brown

The higher up I climbed, the fewer people like me I saw. When I say like me, I don’t just mean colour of skin. I am a brown skinned woman, from a working-class background, without a degree, in a leadership position. I mean people like me.

Let me take you back to when I was 17 years old. I had just finished my final and only year in school, I was living independently in a youth hostel, juggling a full-time job in a sweet shop and a full-time A Level schedule at college. I also did a bit of club promoting on the side but that’s a story for another day. I knew that something had to give, and I figured it should probably be education, so I spoke to a careers advisor and told her that I had aspirations to set up my own business. She directed me towards administrative jobs, and I wound up applying for a Community Arts Business Apprenticeship at the Bush Theatre. I had no prior experience or knowledge of theatre, but I figured if it had business in the title, it would fast track me and I would get paid at the same time. Win, win.

In the interview, they asked why I wanted the job and I told them I didn’t really know much about theatre, but I loved reading books, listening to music and going to the cinema, so I’m sure I would get the hang of it. I now coach young people for job interviews and if any of them told me they said this, I would probably disown them – but here I was, bright eyed and hungry, with the life experiences of a 30-year-old, but blissfully unaware of the prestigious opportunity in front of me.

I am certain it was the next line that got me the job: ‘I saw on your website that you’re trying to find young people from the local community. I’m a young person, I’ve lived here all my life, but I’ve never heard of you. Maybe I could help you find young people like me?’ Bingo. I’d said the magic words.

It felt like stepping into Narnia. I had lived in Shepherd’s Bush my entire life. The O’Neil’s pub was a regular spot, but I’d never clocked the bright green door on the side of the building that was the entrance to the theatre. But once I saw it, I couldn’t unsee it – and I fell deeply in love with the magic that happened inside.

You see, theatre is an artform like no other. When you produce a film, you refine it until it’s done. Every time you go back to experience it again, the film stays the same but you see new layers because you have changed. Theatre, on the other hand, is alive. An audience can change a play, as much as a play can change an audience. I fell in love with the idea that you can change your narrative; that the labels I had lived with, the trauma I had experienced and the relationships I struggled with, could all be written away.

There’s a story here about how I struggled to fit in. How I spent the first few years of my career feeling like an outsider. Like I didn’t belong there. Like all minorities given a bit of rope, I worked harder than any of my counterparts and didn’t stop there. I used my survival skills to adapt to my new environment and fooled everyone around me – even myself – that I really did belong there. I climbed high and fast and through mentorship, great opportunities and a strong faith, I leapt ahead and created a path for the next generation of leaders behind me.

The price you pay for assimilating, though, is that you strip away part of your identity and ultimately leave the very thing that makes you brilliant at the door. I realise now that my diversity is my superpower and by hiding it, I not only denied myself, but I denied everyone around me. You see, the current leadership in British culture is only reflective of a very slim part of society. It is dominated by people who come from privilege, who are formally educated, pale skinned and mainly identify as male. So, it makes total sense that the work being produced is created through their lens and therefore mostly benefits a small segment of society.

We are changed by what we see; just as we are changed when we are seen.

A year into my apprenticeship I saw a play called Sucker Punch by Roy Williams and a penny dropped. That performance was one of few transformative moments I’ve had in an auditorium where I’ve seen a part of my story, my lived experience, played out on stage. I started to seek out more plays like it but found that it was in a league of its own. That is to say, work by black artists was hard to come by.

So I started to write. I wrote about my experiences and how I saw the world, and I encouraged others to do the same. I started to shape a career that gave platforms to anyone who was considered a minority – an outsider, like me. I developed programmes that trained diverse talent and I produced theatre, events and festivals that showcased the best work I could find – that just happened to be made by an underrepresented artist. I had fire in my belly because I could see the injustice that only a select few got to create and consume art and ‘culture’. I am convinced that creativity – not just theatre, but all art – is transformative, that it’s a powerful tool to unpack, process and reshape the way we see the world and the role that we play and it’s an offence that only a small portion understand this enough to monopolise it.

There has been a shift in the last few years to see more people of colour and disabled artists on stage and screen which I am 100 per cent supportive of. But in truth, I feel like it’s sticking a plaster on an open wound. Until we change the types of people making decisions – of commissioning, of casting, of recruitment, of funding – we won’t actually change anything at all. Just the face of it.

Until there is a diversity of perspectives coming from different walks of life behind the scenes, we will continue to have a narrow approach and view of what the world actually looks like. It’s just common sense: a diverse group of people will outperform a homogenous group because they have a wider range of skills, knowledge and experiences to draw from.

But we can’t stop there. It’s really easy to hire a few people who look and sound different to you and then expect to see instant results. But it just doesn’t work like that. If we want to reap the benefits of having a broader, richer British culture for all to consume then we need to be bolder and find the answer to why this hasn’t already happened. What is it about mainstream culture that is preventing diversity from thriving? And what is my role – what are all of our roles – in addressing this?

Diversity is being invited to the party. Inclusion is being asked to dance.

If the majority of British culture is set up to benefit a small segment of society, then why wouldn’t this also apply to the systems, processes and languages used across broader society too? Applying a holistic lens to inclusion benefits everyone – even those who are currently thriving. Only when we truly diversify the experiences we share with one another will we have an equitable playing field with rich narratives that reflect the whole of society, and the true diversity of great British culture. And only then will we know what real community, and real connection, can mean.

Sade Brown is the Founder and CEO of Sour Lemons which seeks to increase diverse leadership within the creative, cultural and social sectors. She is also resident social entrepreneur at UnLtd.

This article is part of the pamphlet Finding connection in a disconnected age: stories of community in a time of change, published in partnership with Nesta.